Intern Ultrasound of the Month: Pneumothorax

The Case

83-year-old male with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) presented to the emergency department (ED) for pleuritic chest pain and shortness of breath that started after a coughing fit. He reported two weeks of flu-like symptoms prior to this. He arrived to the ED on a non-rebreather, slightly tachypneic but satting well and otherwise well-appearing.

Lung ultrasound was performed and showed the following:

Anterior chest - no sliding visualized

Subtle lung point - absent sliding (left) meets sliding (right)

Normal lung sliding (lateral and inferior chest)

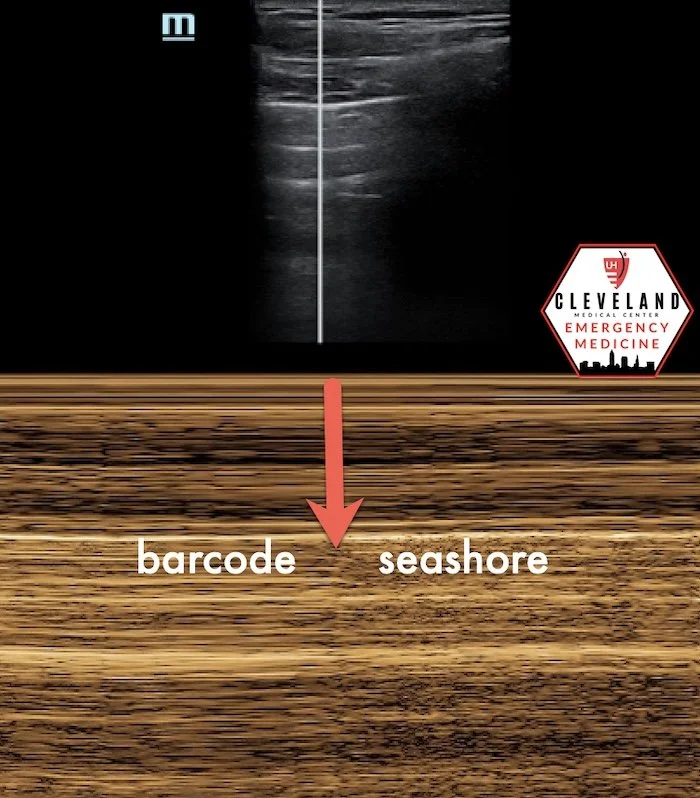

POCUS Findings: Lung ultrasound demonstrated a lung point, representing the interface between normal pleural sliding and absent sliding, consistent with pneumothorax and helpful for localizing its extent. In addition, M-mode (not shown here) demonstrated a transition from seashore sign to barcode sign, corresponding to normal lung sliding and absent lung sliding, respectively — see representative example below.

Case Conclusion: The patient underwent chest tube placement in the ED with imaging guidance to optimize insertion site selection, and he tolerated the procedure well. He experienced symptomatic improvement and was admitted to the hospital, where he was successfully weaned off supplemental oxygen and had an uncomplicated course.

Pneumothorax

Overview

A pneumothorax is the presence of air within the pleural space, external to the lung parenchyma, which can lead to partial or complete lung collapse. Pneumothoraces are classified as simple, tension, or open. A simple pneumothorax does not cause mediastinal shift, whereas a tension pneumothorax results in progressive intrathoracic pressure with mediastinal displacement and hemodynamic compromise. An open pneumothorax, commonly referred to as a “sucking” chest wound, occurs when air freely enters the pleural space through a chest wall defect, communicating with the external environment (1).

Epidemiology

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) most commonly occurs in individuals aged 20-30 years, with an annual incidence of approximately 7 per 100,000 men and 1 per 100,000 women in the United States (2). Recurrence is common, occurring in 25-50% of patients, with the highest risk within the first year, and particularly early after the initial event (1-3).

Secondary spontaneous pneumothorax (SSP) typically occurs in older adults (60–65 years) and is associated with underlying lung disease (1,3). The incidence is approximately 6.3 per 100,000 men and 2 per 100,000 women, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 3:1 (3). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major risk factor for SSP (1). Heavy tobacco use markedly increases pneumothorax risk, with rates reported to be substantially higher than in non-smokers (1,3).

Diagnostic Imaging

Computed tomography (CT) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing pneumothorax (1). However, when performed by experienced operators, lung ultrasound is often more sensitive than chest radiography, allows for rapid bedside diagnosis and avoids ionizing radiation, making it particularly valuable in acute and resuscitative settings (4-6).

Lung Ultrasound

Lung ultrasound is one of the most commonly used applications of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in the ED and has gained widespread adoption over the past decade. It can be utilized to evaluate a wide range of pathologies, including pneumothorax, pleural effusion, pulmonary edema, pneumonia, and atelectasis (7,8). While lung ultrasound should not delay definitive management, such as emergent operative intervention or other life-saving measures, it is a low-risk examination with no significant contraindications (7).

Image Acquisition

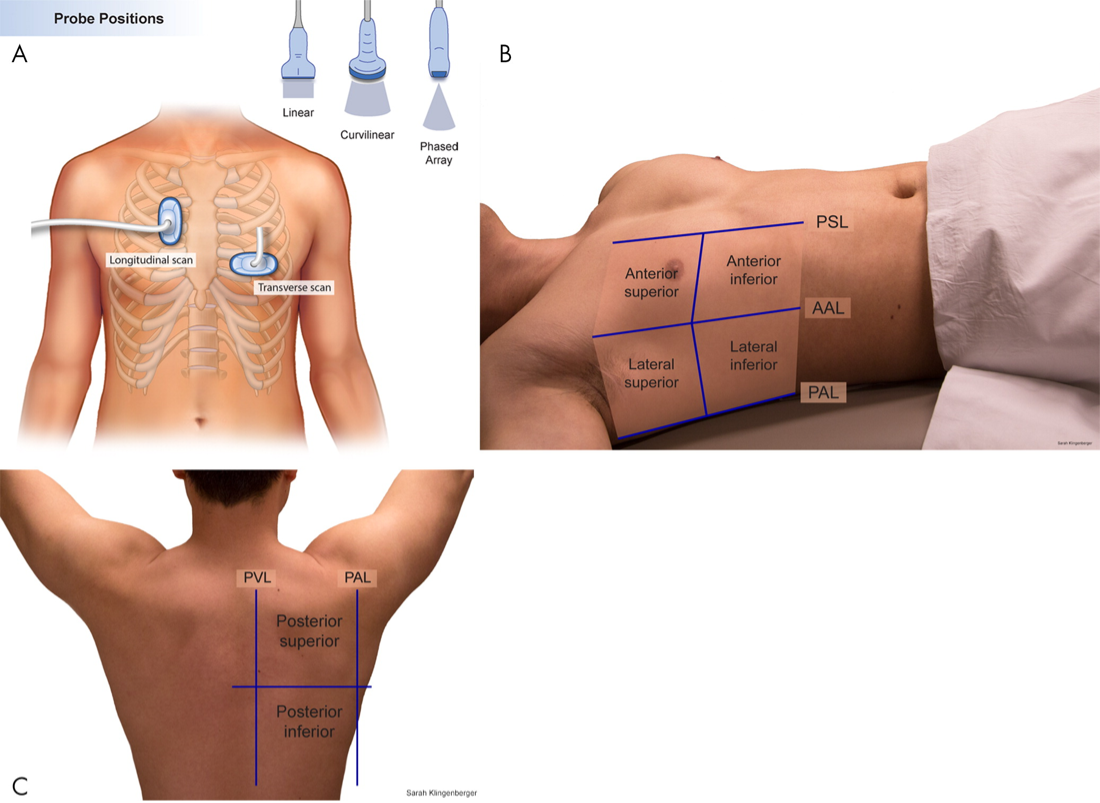

A comprehensive lung ultrasound examination involves assessment of each hemithorax across the anterior, lateral, and posterior lung zones, in both transverse and longitudinal orientations (7,8), see Figure 1. In emergency settings, a focused, clinical question–driven approach is often sufficient and should be tailored to the clinical context and patient positioning (7). Curvilinear probes (5–9 MHz) are well-suited for general lung assessment, while high-frequency linear probes (7–12 MHz) provide superior resolution of superficial structures and are particularly useful in pediatric patients and when assessing for pneumothorax (7,8). Switching to a linear probe can be especially helpful when findings are subtle, improving visualization of lung sliding or a suspected lung point.

Because lung ultrasound is largely artifact-based, the probe should be held perpendicular to the skin to optimize artifact generation and interpretation (8). Larger body habitus may limit visualization of the pleural line and deeper structures.

Figure 1. Lung zones (obtained from RSNA.org, adapted from Marini et al. (8)

Assessing for Pneumothorax

Assessment for pneumothorax on lung ultrasound centers on evaluation of pleural motion rather than direct visualization of intrapleural air (7,8). After identifying the pleural line, first assesses for pleural sliding (Figure 2), which reflects normal apposition of the visceral and parietal pleura; its presence effectively rules out pneumothorax at that location (5,7). Because air preferentially accumulates in the least dependent regions of the lung, focusing the initial assessment in these areas provides the highest diagnostic yield.

When pleural sliding is absent (figure 3), pneumothorax should be considered; however, this finding alone is not diagnostic, as absent sliding may also be seen in apnea, mainstem intubation, pleurodesis, or severe underlying lung disease. In this setting, additional features — such as B-lines or a lung pulse (pulse-like pleural movement synchronous with cardiac activity, see figure 4) — indicate apposition of the visceral and parietal pleura, arguing against pneumothorax and prompting consideration of alternative explanations for absent pleural sliding (7,9).

When findings that argue against pneumothorax are absent, or when the clinical context remains concerning, the probe should be moved laterally and posteriorly to search for the lung point, which is highly specific for pneumothorax (10,11).

Figure 2. Normal lung sliding

Figure 3. Absent lung sliding

Figure 4. Lung pulse

Key Diagnostic Finding: The Lung Point

The lung point represents the interface between normally aerated lung and pneumothorax, with pleural sliding present on one side and absent on the other (10), see figure 5. The lung point has a reported sensitivity of approximately 66% and a specificity approaching 100% for pneumothorax (11).

M-mode can help confirm a lung point by demonstrating a transition from the barcode sign to the seashore sign as the pleural interface alternates between absent and normal sliding (figure 6).

Figure 5. Lung point

Figure 6. M-mode example illustrating barcode-to-seashore transition at the lung point

Estimating Pneumothorax Size

Because larger pneumothoraces are more likely to require thoracostomy, identifying the location of the lung point can help estimate pneumothorax size. If lung sliding is absent anteriorly, the probe can be moved laterally and posteriorly to identify the lung point. The more lateral or posterior the lung point, the larger the pneumothorax; conversely, an anterior lung point indicates a smaller pneumothorax (10,11).

Lung Point Mimics

Several entities may mimic a true lung point and should be interpreted within clinical context. A physiologic lung point may occur near the mediastinal border, where cardiac motion simulates pleural movement (12). In patients with bullous lung disease, a lung-point-like appearance may be seen at the interface between a bulla and aerated lung. This occurs only when subpleural lung tissue is completely absent beneath the pleura; even a thin preserved layer prevents this artifact. Differentiation requires integration of ultrasound findings with the clinical picture (9,13).

Take-Home Points

Lung ultrasound is a rapid, low-risk bedside tool for pneumothorax detection

A complete exam includes multiple zones and probe orientations, though focused exams are often sufficient

The lung point is highly specific for pneumothorax

Lung point location helps estimate pneumothorax size and guide chest tube decision-making

Ultrasound findings must always be interpreted in clinical context, particularly in bullous lung disease

AUTHORED BY: JORDAN DEANGELIS, DO

FACULTY EDITING BY: LAUREN MCCAFFERTY, MD

References

McKnight CL, Burns B. Pneumothorax. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441885/Melton LJ, Hepper NG, Offord KP. Incidence of spontaneous pneumothorax in Olmsted County, Minnesota: 1950-1974. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120(6):1379-1382.

Gupta D, Hansell A, Nichols T, Duong T, Ayres JG, Strachan D. Epidemiology of pneumothorax in England. Thorax. 2000;55(8):666-671.

Goel A, Carroll D, Fortin F, et al. Pneumothorax (ultrasound). Radiopaedia.org.

https://radiopaedia.org/articles/pneumothorax-ultrasound-1Chan SS. Emergency bedside ultrasound to detect pneumothorax. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(1):91-94.

Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(4):577–591.

Taylor A, Anjum F, O’Rourke MC. Thoracic and lung ultrasound. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK500013/Marini TJ, Rubens DJ, Zhao YT, Weis J, O’Connor TP, Novak WH, Kaproth-Joslin KA. Lung ultrasound: technique, findings, and clinical applications. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2021;3(2):e200564.

Skulec R, Pařízek T, David M, Matoušek V, Černý V. Lung point sign in ultrasound diagnostics of pneumothorax: imitations and variants. Emerg Med Int. 2021;2021:6654272.

Emory University Department of Emergency Medicine. Lung Point.

https://med.emory.edu/departments/emergency-medicine/sections/ultrasound/case-of-the-month/lung/lung-point.htmlHusain LF, Hagopian L, Wayman D, Baker WE, Carmody KA. Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2012;5(1):76-81.

Zhang Z, Chen L. A physiological sign that mimics lung point in critical care ultrasonography. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):155.

Matoušek V, Zemanová P, Stach Z. Pneumothorax, which was not a pneumothorax. J Anesth Intensive Care Med. 2021;32(1):48-51.