Resus: Three Applications for Agitated Saline Ultrasonography in Resuscitation

Introduction

Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) has become established as an essential diagnostic modality for both the ED and ICU, allowing clinicians real time insight into patient physiology and guiding technique for procedures including central venous catheter insertion. The addition of agitated saline (AS) to the POCUS tool kit offers expanded capabilities for faster, more informed patient care at the bedside including confirmation of central line placement, assessment of right heart function and detecting right to left cardiac shunting.

Background

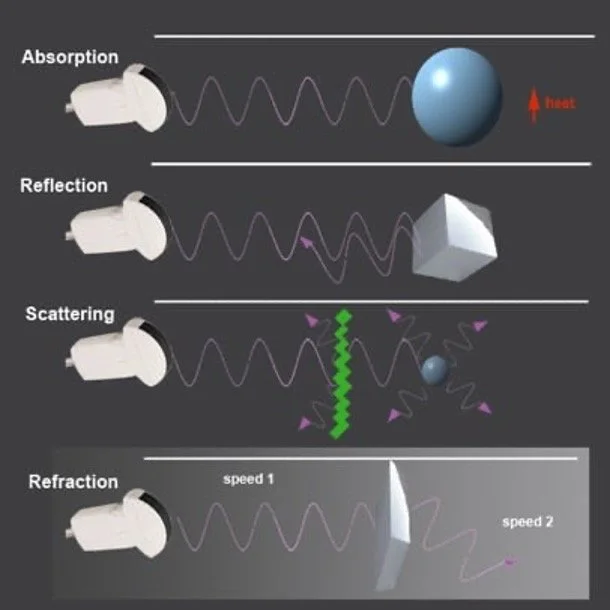

The images created by ultrasound are the result of sound waves transmitted by the ultrasound probe scattering as they interact with different media; some scattered waves return to the probe and are detected by the probe’s piezoelectric crystal array. The degree to which a structure is visible to ultrasound is a function of how much scatter and reflection of sound waves it causes (Figure 1). Higher density substances (muscle) create significantly more sound wave reflection and scatter and therefore brighter images while lower density substances (blood or lung) produce a darker image because sound waves are transmitted or refracted rather than scattering. Because of this ultrasound is highly effective in highlighting interfaces between solid, liquid, and gaseous phases in the body such as identifying blood vessels within soft tissue or the junction between the pleural border the chest wall (1,2).

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the modes in which ultrasound waves may interact with material. Image from ACEP Sonoguide (2).

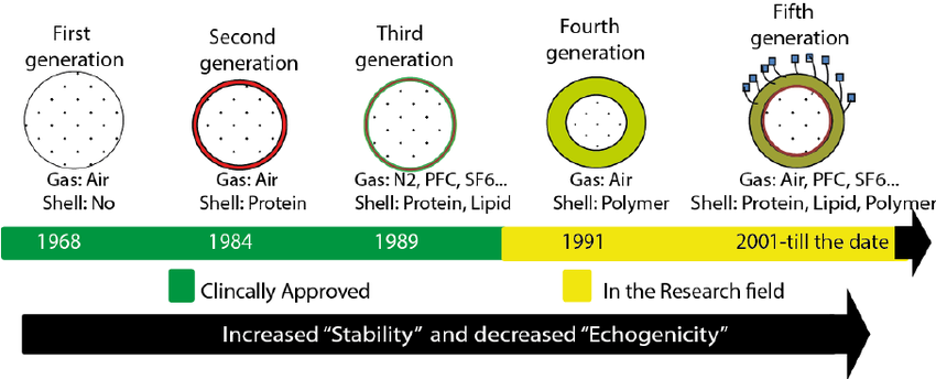

Microbubbles enhance ultrasound imaging by increasing the echogenicity of the vasculature as they create numerous micro-interfaces between the surrounding medium (blood) and the air or other gas contained in the bubble. Since initial trials of agitated saline (AS) showed improvement the quality of echocardiography in 1968, ultrasound enhancing agents (UEAs) have become a widely accepted supplement to cardiovascular imaging (3). Per the guidelines by the American society of Echocardiography (ASE) in 2018 a wide array of UEAs with a variety of shells and gaseous components have demonstrated safety and efficacy for detecting cardiac pathology including agents such as activated perfluorocarbon, sulfur hexafluoride microbubbles in a phospholipid shell and activated nanoparticles (see Figure 2) (1,3–5). Significant advances in UEAs notwithstanding, AS is still favored in the acute setting due to its widespread availability, low cost, and relative simplicity of use.

Figure 2: Evolution of microbubble ultrasound enhancing agents from first use to present (5).

Technique

Note: Although relevant to all of the applications of AS described here, these methods were reported for use of AS to detect PFO and right to left cardiac shunt.

Unlike many commercially available UEAs whose external capsules are disrupted by passage through an IV catheter AS, which has no capsule and may be injected through relatively small-bore peripheral IVs. Other than central venous access, a 20g or larger IV catheter at or proximal to the antecubital fossa is the most studied administration technique although hand IVs have also been reported (1).

Figure 3: Set up and supplies for AS administration including saline flush, syringe containing a small volume of room air, three-way stopcock, J-loop, and venous access (20g peripheral IV angio catheter shown).

In the set up described for evaluation of right to left shunting, a syringe containing 9 – 9.5 mL of normal saline and a syringe containing 1.0 – 1.5 mL of room air are connected to the three-way stopcock (see Figure 3). Adequate agitation can be achieved by vigorously mixing the contents of the two syringes back and forth with the stopcock closed to the J-loop and venous access. Luer Locks on the syringes were recommended to avoid accidental leakage during mixing. Once unform bubbles form and no large air pockets are visible, the mixture should be injected rapidly into venous access followed by a normal saline flush to facilitate rapid travel of AS to desired location while bubbles are intact (1).

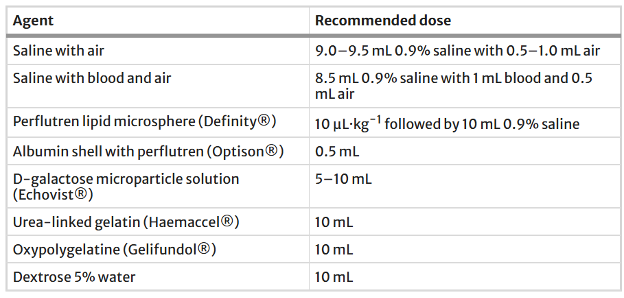

Variations exist on AS additives on composition and other UEAs; evidence exists for improved bubble stability by including 1 mL of aspirated blood from the patient (see Table 1).

Table 1: Various ultrasound enhancing agents and their recommended dosages(1,3).

When examining the right heart as well as confirming central line placement, authors recommend that injection be performed by an assistant while another clinician or sonographer maintained the desired view with the ultrasound probe to capture real time bubble-enhanced images (1,6)

Applications:

1. Confirming central line placement.

Central venous access is foundational to resuscitation care provision of lifesaving vasoactive medications and large volumes of fluids. POCUS has long been used to guide central venous catheter (CVC) insertion which has contributed to improved safety (7). However, for supradiaphragmatic CVCs acute mechanical complications of line placement are still relatively common including misplaced catheter tip (5% - 9% reported incidence), pneumothorax (reported incidence up to 3.3%) and arterial puncture (reported incidence of 8.4%) (6–8).

Currently the standard for ensuring correct placement is portable chest X-ray (CXR). Even in resource rich settings, X-ray is rarely immediately available in both the ED and ICU, contributing to delays in CVC use for vital patient care. One study found an average delay of 65 minutes between CVC placement and CXR confirmation (6,9). Additionally, there is currently debate on the clinical necessity of classically taught placement of the CVC tip in the lower portion of the SCV. Several studies indicate that alternative placement within venous system including the right atrium, brachiocephalic veins, and subclavian veins are tolerated without additional complications (6,10). The exception to these findings is inadvertent canulation of the contralateral internal jugular vein on a subclavian approach resulting in the catheter tip pointing cephalad. This is problematic due to possible disruption of cranial venous drainage.

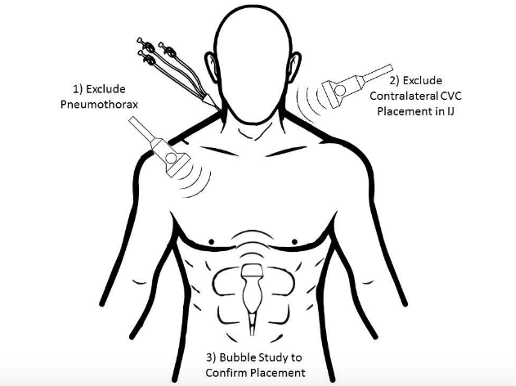

Figure 4: Illustration of POCUS views used to confirm CVC placement and detect pneumothorax and internal jugular placement. Image from ALiEM.com (10).

Since 2015 multiple studies show that AS in combination with the ultrasound techniques already widely used in the ED can be used to confirm CVC placement in the venous system. Similarly, ultrasound can be used to rule out complications including pneumothorax and cephalad IJ cannulation (6,9,11,12). In these studies, CVC placement was confirmed by detection of hyper-echogenicity from rapid saline flushing through the CVC on apical 4 chamber and subcostal views (see Figure 4). Ultrasound was also used to assess lung sliding in order to rule out pneumothorax, and to visualize the contralateral IJ, pericardium and right atrium to locate the catheter tip and rule out IJ canulation and pericardial effusion.

When compared to CXR imaging, several studies showed high levels of concordance in tip location with comparable specificity and sensitivity for complications (6,9,11). In terms of expediting patient care, one study indicated that the total ultrasound time was 23.1 minutes faster than CXR acquisition without a radiology read which was significantly longer. While promising, it is worth noting that all of these studies were used small sample sizes and larger scale trial would be helpful to validate these findings as complications are rare enough that few were captured in these trials.

2. Assessing RV function

Right ventricular dysfunction presents an important clinical challenge in resuscitation and significantly changes both management and prognosis. Echocardiography has long been the standard for diagnosing RV dysfunction. A formal echo may not possible in the acutely ill patient or unstable and conversely POCUS alone is inconsistent as for a reliable assessment of RV function as it is significantly affected provider skill level (13,14).

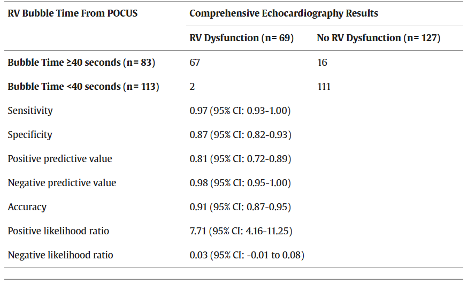

A 2024 study in Annals of Emergency Medicine indicates that the addition of agitated saline to the diagnostic toolbox in the ED setting allows for rapid, more objective measure of RV function. Cohen et al. measured “bubble time” or the interval between agitated saline injection and appearance of bubble hyperechoic artifact in the RV. This was done in an ED convenience sample of patients for whom a comprehensive echocardiogram had already been ordered by their treating physician. Their findings indicate that a bubble time greater than or equal to 40 seconds is 97% sensitive and 87% specific for RV dysfunction when compared to formal echocardiography (see Table 2 summarizing Cohen et al’s test characteristics).

Table 2: From Cohen et al., summary of test characteristics for bubble time greater than 40 seconds (14).

Though it demonstrated exciting potential for objective, timely diagnostic information on the RV, this study was limited by small sample size with only 196 patients. Additionally, all measurements and ultrasounds were performed by a trained sonographer rather than an ED physician which may decrease the transferability of these results between institutions given variable degrees of confidence with ultrasound. Lastly, there was no ability to blind ultrasonographers to patient appearance and presentation during measurement of bubble time which may have introduced a degree of bias.

Overall, agitated saline may offer useful, more objective measure of RV function at the bedside, and more study in the area to test its usefulness in other institutions and patient populations is certainly warranted.

3. Detecting PFO and other intracardiac defects.

Severe sequelae including embolic stroke and refractory hypoxemia can result from patent foramen ovale, atrial septal defects, pulmonary arterio-venous anomalies, and other cardiac or pulmonary anomalies which allow for right to left shunting. Although complications are rare, patent foramen ovale (PFO) can be found in 20-25% of healthy individuals and poses a risk for thromboembolic complications. Inappropriate treatment of acutely ill patients with shunt physiology can result in precipitous decompensation (1,3).

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is currently the gold standard for detecting right to left shunts, and “bubble” studies have been used in the context of formal imaging studies for decades. In both the ICU and ED, an abbreviated version of the bubble study has the potential to rapidly detect of clinically significant intracardiac shunting and expedite appropriate care.

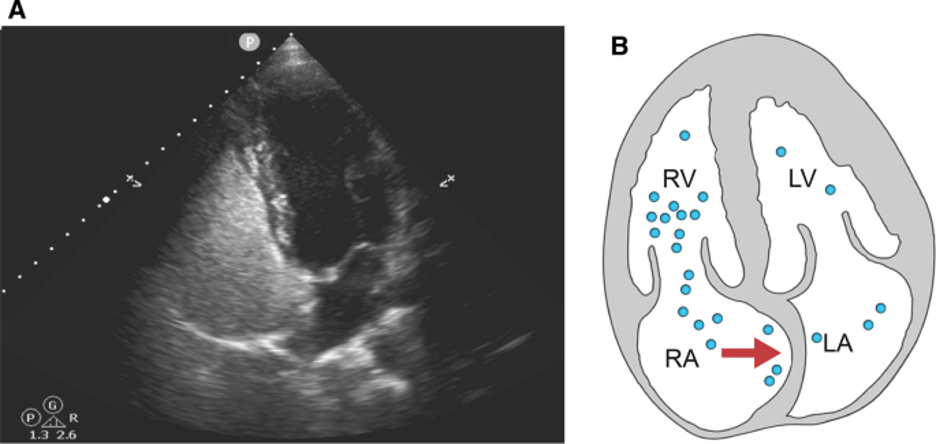

Because the microbubbles in agitated saline are too large to pass through pulmonary circulation, they provide a simple but powerful tool for detecting shunt physiology, as the passage of intact bubbles from the right to left heart most likely indicates a circulatory anomaly bypassing the pulmonary vasculature. In oriented patients, shunt enhancing maneuvers like Valsalva may be used to increase right atrial pressure and briefly exacerbate an existing shunt to improve sensitivity (see Figure 5). In obtunded patients, lung recruiting maneuvers such as briefly applying positive pressure ventilation may function similarly to Valsalva.

Figure 5: Apical 4 chamber view on ultrasound (A) and schematic (B) during Valsalva demonstrating atrial septum bowing. Image from the Montrief et al’s review on POCUS for detection of right to left cardiac shunting(1).

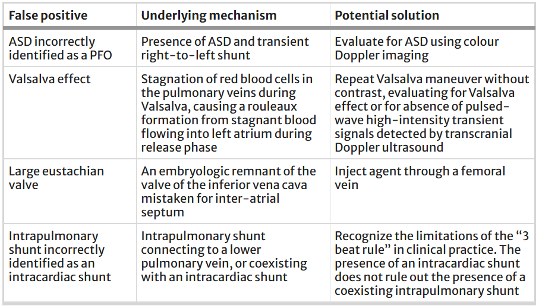

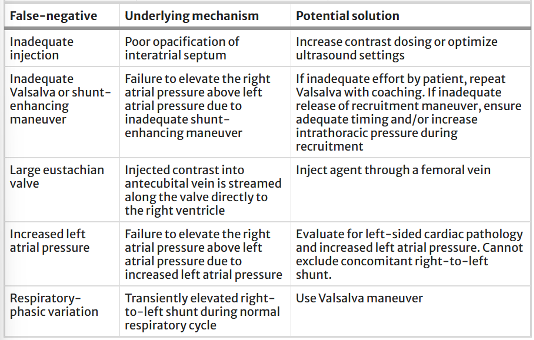

Although agitated saline may be clinically useful for detecting shunts in the acute setting, there are also several limitations to this technique. Several mechanisms may lead to false positive or false negative interpretations of bubble studies (See Tables 3 and 4 for common inaccuracies and proposed solutions).

Table 3: Summary of false positive mechanisms for POCUS assessment of various right to left shunts and proposed solutions. Table from Montreif et al (1)

Table 4: Summary of false negatives mechanisms for POCUS assessment of various right to left shunts and proposed solutions. Table from Montreif et al (1)

Given the need for detailed classification of right to left shunts and cardiac anatomy for definitive care, formal echocardiography and buble studies will remain an essential element of diagnosis. However, agitated saline may allow for a rapid assessment of the shunt clinically significant physiology saline in the acute setting.

AUTHORED BY: GRACE VAN HARE, MS4

FACULTY EDITING BY: COLIN MCCLOSKEY, MD

References

Montrief T, Alerhand S, Denault A, Scott J. Point-of-care echocardiography for the evaluation of right-to-left cardiopulmonary shunts: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67(12):1824-1838.

Au AK, Zwank MD. Sonoguide: Physics and Technical Facts for the Beginner. American College of Emergency Physicians; 2020.

Soliman OI, Geleijnse ML, Meijboom FJ, Nemes A, Kamp O, Nihoyannopoulos P, et al. The use of contrast echocardiography for the detection of cardiac shunts. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2007;8(3 suppl):S2-S12.

Porter TR, Mulvagh SL, Abdelmoneim SS, Becher H, Belcik JT, Bierig M, et al. Clinical applications of ultrasonic enhancing agents in echocardiography: 2018 American Society of Echocardiography guidelines update. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31(3):241-274.

Kothapalli S. Ultrasound contrast agents loaded with magnetic nanoparticles: acoustic and mechanical characterization. Thesis. Washington University School of Medicine; 2013.

Duran-Gehring PE, Guirgis FW, McKee KC, Goggans S, Tran H, Kalynych CJ, et al. The bubble study: ultrasound confirmation of central venous catheter placement. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(3):315-319.

Nayeemuddin M, Pherwani AD, Asquith JR. Imaging and management of complications of central venous catheters. Clin Radiol. 2013;68(5):529-544.

Kornbau C, Lee KC, Hughes GD, Firstenberg MS. Central line complications. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2015;5(3):170-178.

Zanobetti M, Coppa A, Bulletti F, Piazza S, Nazerian P, Conti A, et al. Verification of correct central venous catheter placement in the emergency department: comparison between ultrasonography and chest radiography. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8(2):173-180.

Montrief TMM. Trick of the trade: bubble study for confirmation of central line placement. Academic Life in Emergency Medicine. Published 2019.

Oliveira L, Pilz L, Tognolo CM, Bischoff C, Becker KA, Oliveira GG, et al. Comparison between ultrasonography and X-ray as evaluation methods of central venous catheter positioning and their complications in pediatrics. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36(5):563-568.

Liu YT, Bahl A. Evaluation of proper above-the-diaphragm central venous catheter placement: the saline flush test. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29(7):842.e1-842.e3.

Hockstein MA, Haycock K, Wiepking M, Lentz S, Dugar S, Siuba M. Transthoracic right heart echocardiography for the intensivist. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36(9):1098-1109.

Cohen A, Li T, Bielawa N, Nello A, Gold A, Gorlin M, et al. Right ventricular “bubble time” to identify patients with right ventricular dysfunction. Ann Emerg Med. 2024;84(2):182-194.